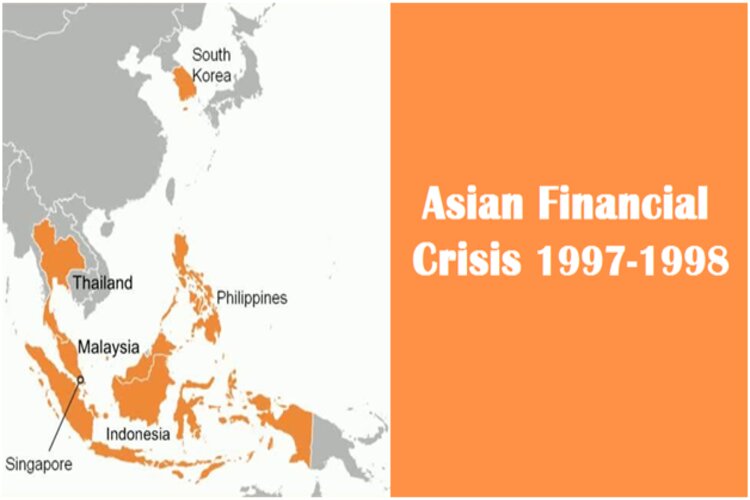

The Asian Financial Crisis is a crisis caused by the collapse of the currency exchange rate and hot money bubble. It started in Thailand in July 1997 and swept over East and Southeast Asia. The financial crisis heavily damaged currency values, financial markets, and other asset prices in many East and Southeast Asian countries. On July 2, 1997, the Thai government ran out of foreign currency. No longer able to support its exchange rate, the government was forced to float the Thai baht, which was pegged to the U.S. dollar before. The currency exchange rate of the baht thus collapsed immediately. The crisis assumed epic proportions. This is because it started in only one country i.e. Thailand whose currency faced an attack from speculators.

Two weeks later, the Philippian peso and Indonesian rupiah underwent major devaluations as well. The crisis spread internationally, and Asian stock markets plunged to their multi-year lows in August. The capital market of South Korea maintained relatively stable until October. However, the Korean won dropped to its new low on October 28th, and the stock market experienced its biggest one-day drop to that date on November 8th. However, in a very short span of time the crisis had gripped the entire South East Asian region. Countries like Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia all got involved in this crisis which almost appeared without any prior warnings. This phenomenon of the crisis spreading quickly to multiple countries is called the “Asian contagion”.

In this article, we will discuss about this events in detail.

Causes of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis

The causes of the Asian financial crisis are complex and controversial. During the late 1980s and early 1990s, many Southeast Asian countries, including Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and South Korea, achieved massive economic growth of an 8% to 12% increase in their gross domestic product (GDP). The achievement was known as the “Asian economic miracle.” However, a significant risk was embedded in the achievement.

The economic developments in the countries mentioned above were mainly boosted by export growth and foreign investment. These countries showed impressive growth rates and foreign capital inflows and were known as ‘tiger economies.’ Therefore, high interest rates and fixed currency exchange rates (pegged to the U.S. dollar) were implemented to attract hot money. Also, the exchange rate was pegged at a rate favorable to exporters. However, both the capital market and corporate were left exposed to foreign exchange risk due to the fixed currency exchange rate policy. Due to massive capital inflows, the asset prices in these countries inflated. There was a boom in the real estate, corporate sector, and the stock market. It was an ‘economic bubble’ that had to burst at some point.

In the mid-1990s, following the recovery of the U.S. from a recession, the Federal Reserve raised the interest rate against inflation. The higher interest rate attracted hot money to flow into the U.S. market, leading to an appreciation of the U.S. dollar.

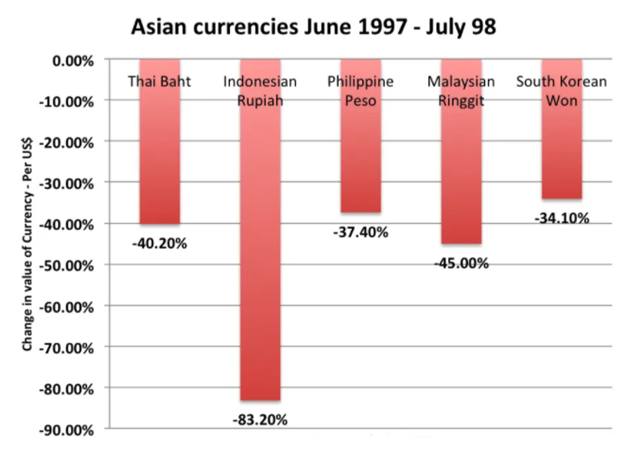

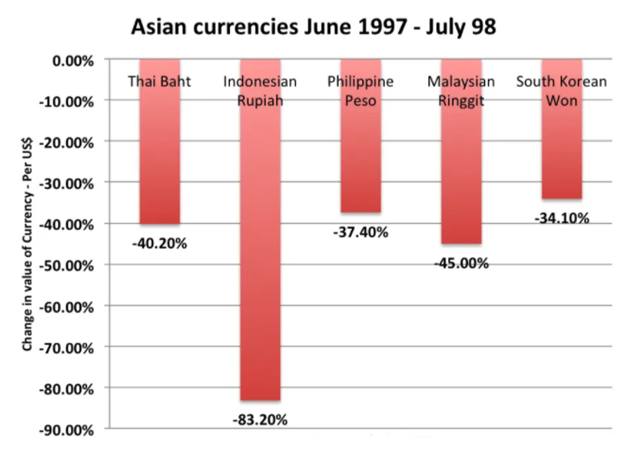

The currencies pegged to the U.S. dollar also appreciated, and thus hurt export growth. With a shock in both export and foreign investment, asset prices, which were leveraged by large amounts of credits, began to collapse. The panicked foreign investors began to withdraw.

The massive capital outflow caused a depreciation pressure on the currencies of the Asian countries. The Thai government first ran out of foreign currency to support its exchange rate, forcing it to float the baht. The value of the baht thus collapsed immediately afterward. The same also happened to the rest of the Asian countries soon after.

Global Effects

The Asian crisis hit investor confidence in the US, though lower interest rates helped to stabilise US economy. China was largely insulated from the crisis because China had attracted physical capital investment and did not rely on foreign flows of capital. The crisis had a negative effect on Japan’s economy and they struggled with a decade of low growth.

Reconstructing the Asian Economy

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is an international organization that promotes global monetary cooperation and international trades, reduces poverty, and supports financial stability. The IMF’s support was conditional on a series of economic reforms, the “structural adjustment package” (SAP). The SAPs called on crisis-struck nations to reduce government spending and deficits, allow insolvent banks and financial institutions to fail, and aggressively raise interest rates. The reasoning was that these steps would restore confidence in the nations’ fiscal solvency, penalize insolvent companies, and protect currency values. Above all, it was stipulated that IMF-funded capital had to be administered rationally in the future, with no favored parties receiving funds by preference. In at least one of the affected countries the restrictions on foreign ownership were greatly reduced.

The IMF generated several bailout packages for the most affected countries during the financial crisis. It provided packages of around $20 billion to Thailand, $40 billion to Indonesia, and $59 billion to South Korea to support them, so they did not default. The countries that received the SAP packages were asked to reduce their government spending, allow insolvent financial institutions to fail, and raise interest rates aggressively. The purpose of the adjustments was to support the currency values and confidence over the countries’ solvency.

Lessons Learned from the Asian Financial Crisis

One lesson that many countries learned from the financial crisis was to build up their foreign exchange reserves to hedge against external shocks. Many Asian countries weakened their currencies and adjusted economic structures to create a current account surplus. The surplus can boost their foreign exchange reserves.

The Asian Financial Crisis also raised concerns about the role that a government should play in the market. Supporters of neoliberals’ promote free-market capitalism. They considered the crisis as a result of government intervention and crony capitalism.

The conditions that IMF set within their structural-adjustment packages also aimed to weaken the relationship between the government and capital market in the affected countries, and thus to promote the neoliberal model.

By 1999, many of the countries the crisis affected showed signs of recovery and resumed gross domestic product (GDP) growth. Many of the countries saw their stock markets and currency valuations dramatically reduced from pre-1997 levels, but the solutions imposed set the stage for the re-emergence of Asia as a strong investment destination.

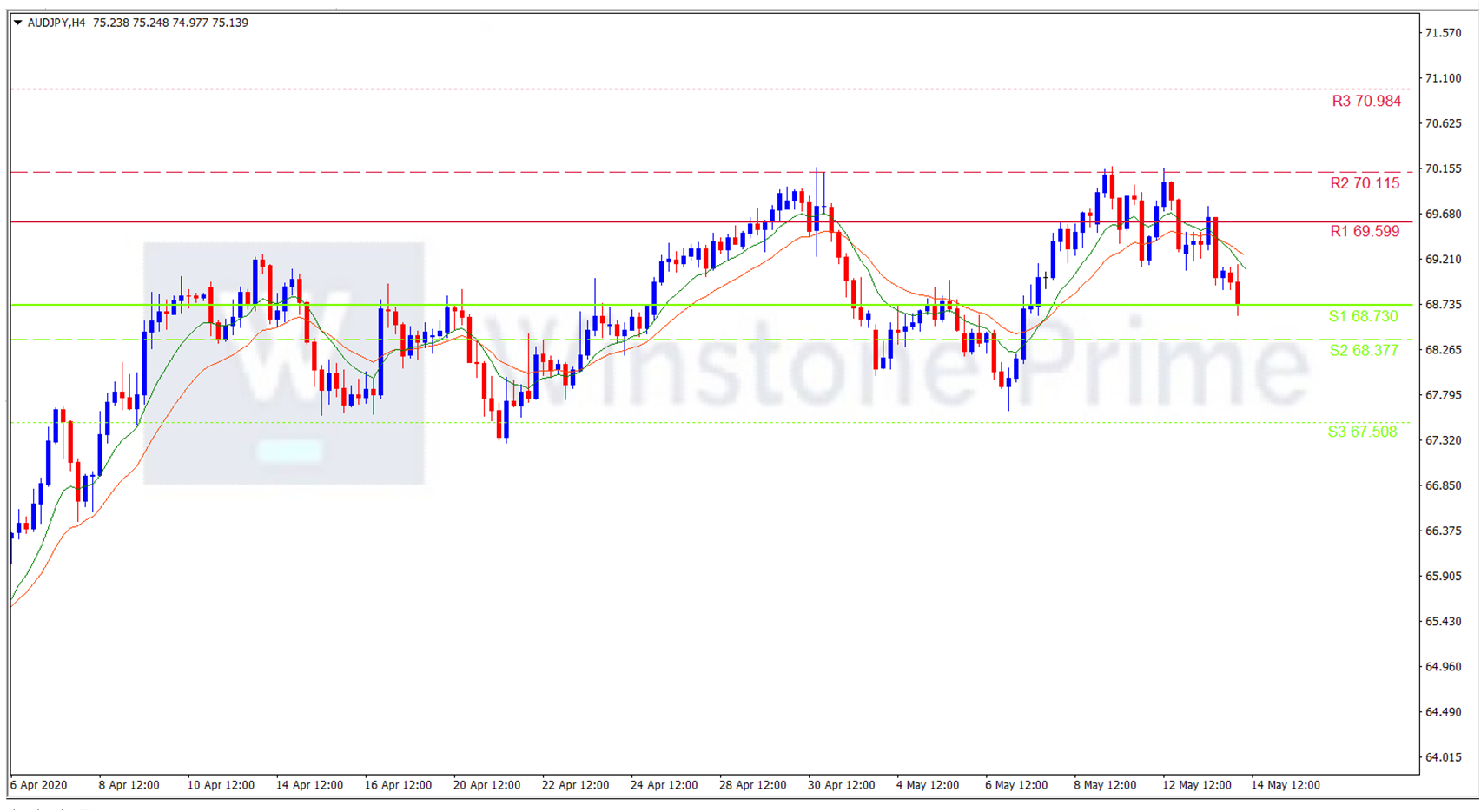

Support: 68.730 (S1), 68.377 (S2), 67.508 (S3).

Support: 68.730 (S1), 68.377 (S2), 67.508 (S3).

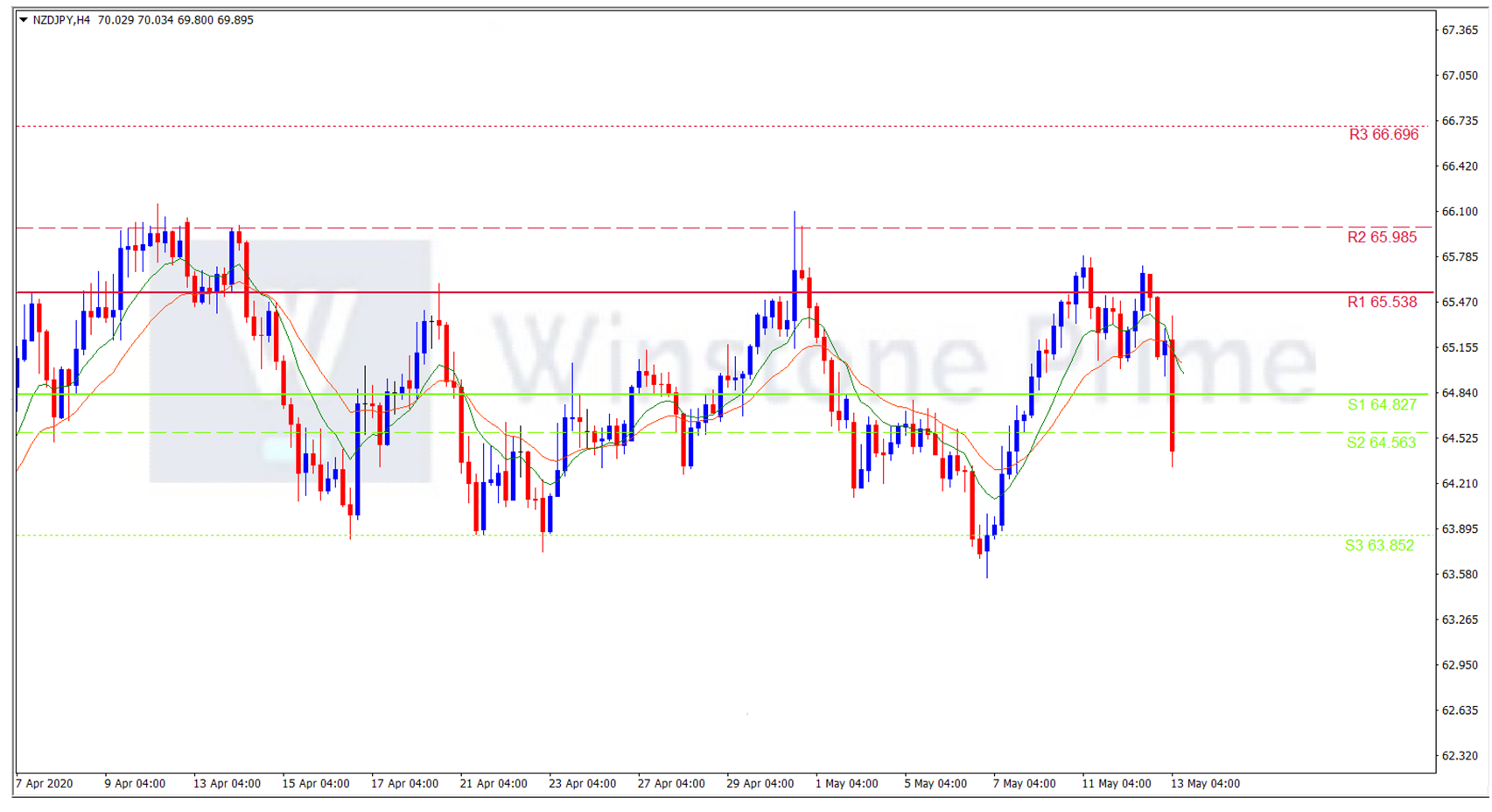

Support: 64.827 (S1), 64.563 (S2), 63.852 (S3).

Support: 64.827 (S1), 64.563 (S2), 63.852 (S3).