The gold standard was a monetary system that was widely prevalent before the concept of fiat money came in. Under this system, the value of a country’s currency or paper money was directly associated with gold. So, under the gold standard, you could convert money into a set amount of gold, as decided by your country. For instance, the pound sterling which was defined as 1/4th of a gold ounce was always exchanged for five U.S. dollars which was defined as 1/20th of a gold ounce. This monetary system was given up by all countries decades ago. Great Britain abandoned the gold standard in 1931, and the US started down that same path in 1933 before the Vietnam War completely brushed it aside in 1971.

It is a well-known fact that gold price is a function of demand and supply. Before the gold standard was given up, the demand for gold was supported by it. Therefore, it is interesting to note the shift in gold price before 1971 and post it. After 1971, the price of gold went sideways for decades, until the global financial crisis of 2009.

Before the rise of Gold standard

For 5,000 years, gold’s combination of luster, malleability, density and scarcity has captivated humankind like no other metal. In ancient times gold is so dense that one ton of it can be packed into a cubic foot. At the start of this obsession, gold was solely used for worship, demonstrated by a trip to any of the world’s ancient sacred sites. Today, gold’s most popular use is in the manufacturing of jewelry. Around 700 B.C., gold was made into coins for the first time, enhancing its usability as a monetary unit. Before this, gold had to be weighed and checked for purity when settling trades. Gold coins were not a perfect solution, since a common practice for centuries to come was to clip these slightly irregular coins to accumulate enough gold that could be melted down into bullion. In 1696, the Great Recoinage in England introduced a technology that automated the production of coins and put an end to clipping.

Since it could not always rely on additional supplies from the earth, the supply of gold expanded only through deflation, trade, pillage or debasement. The discovery of America in the 15th century brought the first great gold rush. Spain’s plunder of treasures from the New World raised Europe’s supply of gold by fives times in the 16th century. Subsequent gold rushes in the Americas, Australia, and South Africa took place in the 19th century. Europe’s introduction of paper money occurred in the 16th century, with the use of debt instruments issued by private parties. While gold coins and bullion continued to dominate the monetary system of Europe, it was not until the 18th century that paper money began to dominate.

The struggle between paper money and gold would eventually result in the introduction of a gold standard.

The Rise of the Gold Standard

The gold standard is a monetary system in which paper money is freely convertible into a fixed amount of gold. In other words, in such a monetary system, gold backs the value of money. Between 1696 and 1812, the development and formalization of the gold standard began as the introduction of paper money posed some problems. The U.S. Constitution in 1789 gave Congress the sole right to coin money and the power to regulate its value. Creating a united national currency enabled the standardization of a monetary system that had up until then consisted of circulating foreign coin, mostly silver.

With silver in greater abundance relative to gold, a bimetallic standard was adopted in 1792. While the officially adopted silver-to-gold parity ratio of 15:1 accurately reflected the market ratio at the time, after 1793 the value of silver steadily declined, pushing gold out of circulation, according to Gresham’s law.

The issue would not be remedied until the Coinage Act of 1834, and not without strong political animosity. Hard money enthusiasts advocated for a ratio that would return gold coins to circulation, not necessarily to push out silver, but to push out small-denomination paper notes issued by the then-hated Bank of the United States. A ratio of 16:1 that blatantly overvalued gold was established and reversed the situation, putting the U.S. on a de facto gold standard. By 1821, England became the first country to officially adopt a gold standard. The century’s dramatic increase in global trade and production brought large discoveries of gold, which helped the gold standard remain intact well into the next century. As all trade imbalances between nations were settled with gold, governments had strong incentive to stockpile gold for more difficult times. Those stockpiles still exist today.

The international gold standard emerged in 1871 following its adoption by Germany. By 1900, the majority of the developed nations were linked to the gold standard. Ironically, the U.S. was one of the last countries to join. In fact, a strong silver lobby prevented gold from being the sole monetary standard within the U.S. throughout the 19th century. From 1871 to 1914, the gold standard was at its pinnacle. During this period, near-ideal political conditions existed in the world. Governments worked very well together to make the system work, but this all changed forever with the outbreak of the Great War in 1914.

The Fall of the Gold Standard

With World War I, political alliances changed, international indebtedness increased and government finances deteriorated. While the gold standard was not suspended, it was in limbo during the war, demonstrating its inability to hold through both good and bad times. This created a lack of confidence in the gold standard that only exacerbated economic difficulties. It became increasingly apparent that the world needed something more flexible on which to base its global economy.

At the same time, a desire to return to the idyllic years of the gold standard remained strong among nations. As the gold supply continued to fall behind the growth of the global economy, the British pound sterling and U.S. dollar became the global reserve currencies. Smaller countries began holding more of these currencies instead of gold. The result was an accentuated consolidation of gold into the hands of a few large nations.

The stock market crash of 1929 was only one of the world’s post-war difficulties. The pound and the French franc were horribly misaligned with other currencies; war debts and repatriations were still stifling Germany; commodity prices were collapsing; and banks were overextended. Many countries tried to protect their gold stock by raising interest rates to entice investors to keep their deposits intact rather than convert them into gold. These higher interest rates only made things worse for the global economy. In 1931, the gold standard in England was suspended, leaving only the U.S. and France with large gold reserves.

Then, in 1934, the U.S. government revalued gold from $20.67/oz to $35/oz, raising the amount of paper money it took to buy one ounce to help improve its economy. As other nations could convert their existing gold holdings into more U.S dollars, a dramatic devaluation of the dollar instantly took place. This higher price for gold increased the conversion of gold into U.S. dollars, effectively allowing the U.S. to corner the gold market. Gold production soared so that by 1939 there was enough in the world to replace all global currency in circulation.

As World War II was coming to an end, the leading Western powers met to develop the Bretton Woods Agreement, which would be the framework for the global currency markets until 1971. Within the Bretton Woods system, all national currencies were valued in relation to the U.S. dollar, which became the dominant reserve currency. The dollar, in turn, was convertible to gold at the fixed rate of $35 per ounce. The global financial system continued to operate upon a gold standard, albeit in a more indirect manner.

The agreement has resulted in an interesting relationship between gold and the U.S. dollar over time. Over the long term, a declining dollar generally means rising gold prices. In the short term, this is not always true, and the relationship can be tenuous at best, as the following one-year daily chart demonstrates. In the figure below, notice the correlation indicator which moves from a strong negative correlation to a positive correlation and back again. The correlation is still biased toward the inverse (negative on the correlation study) though, so as the dollar rises, gold typically declines.

What Is Fiat Money?

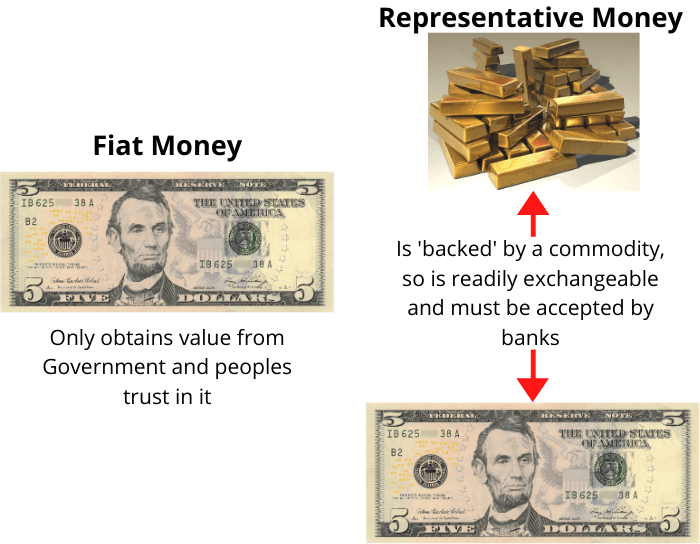

Fiat money is government-issued currency that is not backed by a physical commodity, such as gold or silver, but rather by the government that issued it. The value of fiat money is derived from the relationship between supply and demand and the stability of the issuing government, rather than the worth of a commodity backing it as is the case for commodity money. Most modern paper currencies are fiat currencies, including the U.S. dollar, the euro, and other major global currencies.

Gold Standard System Versus Fiat System

As its name suggests, the term gold standard refers to a monetary system in which the value of currency is based on gold. A fiat system, by contrast, is a monetary system in which the value of currency is not based on any physical commodity but is instead allowed to fluctuate dynamically against other currencies on the foreign-exchange markets. The term “fiat” is derived from the Latin “fieri,” meaning an arbitrary act or decree. In keeping with this etymology, the value of fiat currencies is ultimately based on the fact that they are defined as legal tender by way of government decree.

In the decades prior to the First World War, international trade was conducted on the basis of what has come to be known as the classical gold standard. In this system, trade between nations was settled using physical gold. Nations with trade surpluses accumulated gold as payment for their exports. Conversely, nations with trade deficits saw their gold reserves decline, as gold flowed out of those nations as payment for their imports.

Conclusion

While gold has fascinated humankind for 5,000 years, it hasn’t always been the basis of the monetary system. A true international gold standard existed for less than 50 years—from 1871 to 1914—in a time of world peace and prosperity that coincided with a dramatic increase in the supply of gold. The gold standard was the symptom and not the cause of this peace and prosperity.

Though a lesser form of the gold standard continued until 1971, its death had started centuries before with the introduction of paper money—a more flexible instrument for our complex financial world. Today, the price of gold is determined by the demand for the metal, and although it is no longer used as a standard, it still serves an important function. Gold is a major financial asset for countries and central banks. It is also used by the banks as a way to hedge against loans made to their government and as an indicator of economic health.

Under a free-market system, gold should be viewed as a currency like the euro, yen or U.S. dollar. Gold has a long-standing relationship with the U.S. dollar, and, over the long term, gold will generally have an inverse relationship. With instability in the market, it is common to hear talk of creating another gold standard, but it is not a flawless system. Viewing gold as a currency and trading it as such can mitigate risks compared with paper currency and the economy, but there must be an awareness that gold is forward-looking. If one waits until disaster strikes, it may not provide an advantage if it has already moved to a price that reflects a slumping economy.

Happy Trading